Peadar O’Callaghan: A MONUMENTAL HIERATIC IMAGE

Many dramatic media images with accompanying captions from events of this weekend coming not only from Gaza, the Holy Land, but the U.S. will shock people once again. The images cannot be seen apart from the underlying text of the unfolding narratives that all have been witnessing for far too long. One only hopes and prays that those ministering in these environments and trying to offer hope and consolation for the bereaved and injured will find support for themselves too.

It may seem that concerns about ‘exclusion’ from a eucharistic event expressed by a group of American priests outlined elsewhere in this site pale before these bloody images. But do they?

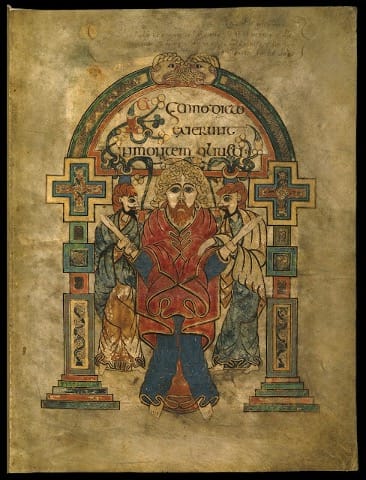

Having attending lectures by the late Dr. Jennifer O’Reilly who lectured on medieval history in University College Cork between 1975 and her retirement in 2008 I came to appreciate the power of image and text especially when put together in the iconography of early Irish and Anglo-Saxon art. Her profound understanding and insight into the images of the Body of Christ in the Book of Kells prompts me to turn again this morning to look again at the image of Christ in fol. 114r in Matthew’s Gospel flanked and touched by two human figures. She says it is a very rare example of a figural image positioned within a gospel text. Some see it as a depiction only of Christ’s arrest in Gethsemane, but it is also possible to look at it as “not a narrative illustration of one event but a monumental hieratic image”.

How difficult the challenge facing priests today to find the Body of Christ within the text of the Roman Missal and in the sharing of paten and chalice.

Reflecting on the image of Christ in Matthew’s Gospel in the Book of Kells may help. Of this image Dr. O’Reilly’s says:

“In the Book of Kells the two columns which flank the two figures are ornamented with vines rising from chalices. As already seen, this was an early Christian motif representing the eucharist and eschatological incorporation of the faithful into Christ. Christ, vested in human flesh, is robed in red; with his priestly gesture of oblation he both evokes his Passion and articulates the text on the facing page: ‘take, eat […] this is my body which is broken for the life of the world’. The image and the text form a diptych, though the image is not a literal illustration of the Last Supper. Rather, it shows the sacramental means by which, since the Resurrection, Christ’s life-giving offering continues to be received and it prompts further meditation on the mystery of the body of Christ, made present at every celebration of the Eucharist. His iconic gaze invites the faithful to draw near into the union with him and with each other.”

Source: Jennifer O’Reilly, ‘The Body of Christ in the Book of Kells’ p. 205-213 in Early Medieval Text and Image 2, Routledge, Variorum Collected Studies Series, 2019.

A beautiful plate of this image can be seen on page 45 of ‘The Book of Kells Reproductions from the Manuscript in Trinity College’ by Françoise Henry, Thames and Hudson, London, 1974. The photography was carried out by John Kennedy, of The Green Studio, Dublin.