NCR Online: Former doctrinal chief calls Father Gustavo Gutierrez ‘one of the great theologians of our time’

Junno Arocho Esteves

Rome — October 23, 2024

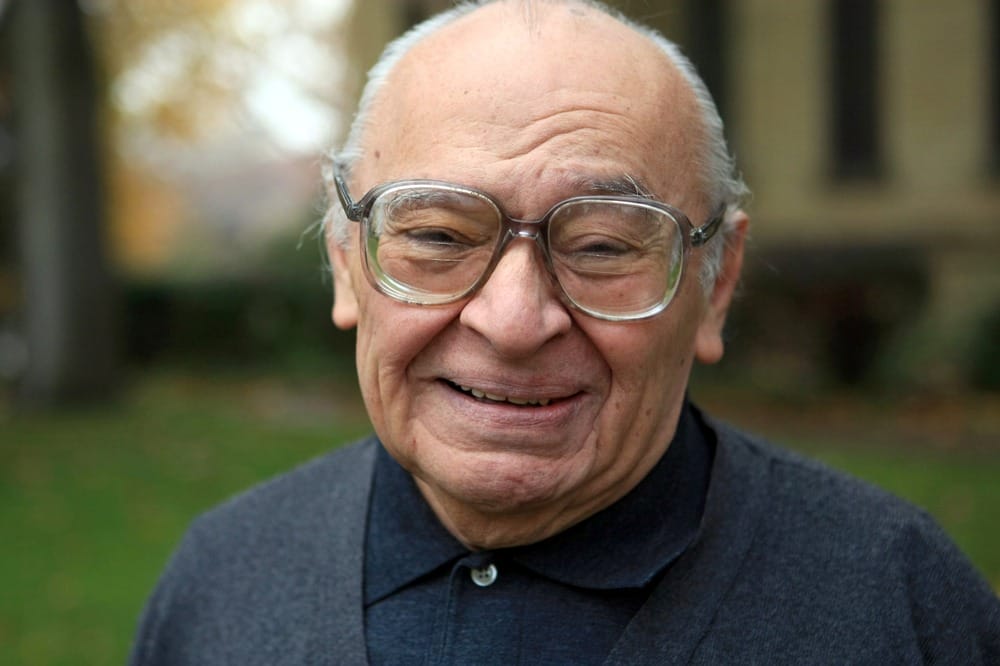

Dominican Father Gustavo Gutiérrez is pictured in 2007 on the campus of the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. Father Gutiérrez, known as the “father of liberation theology,” which rose to prominence in South America in the 1960s and 1970s as a way of responding to the needs of Latin America’s poor, died Oct. 22, 2024, at age 96. (OSV News/Matt Cashore, courtesy University of Notre Dame)

Dominican Father Gustavo Gutiérrez, known as the “father of liberation theology,” which rose to prominence in South America in the 1960s and 1970s as a way of responding to the needs of Latin America’s poor, died Oct. 22 at age 96.

The Dominican Province of St. John the Baptist in Peru, Gutiérrez’s community, announced the theologian’s death Oct. 22 through its Facebook page.

“We ask that you accompany us with your prayers so that our dear brother may enjoy eternal life,” the province posted on the site. The order said his remains would be laid to rest at the 16th-century Monastery of Santo Domingo in Lima.

Among those who mourned the late theologian’s death was his longtime friend German Cardinal Gerhard Müller, former prefect of the then-Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, whose 2014 book “Poor for the Poor: The Mission of the Church,” featured two chapters written by Father Gutiérrez, who he called “one of the great theologians and Catholic personalities of our time.”

“We can learn from him. And also, we are aware that he is not dead, but he is living in heaven with God, in the communion of saints, and he is praying for us and giving us a good example with his life and work,” Müller said in a telephone interview with OSV News Oct. 23.

Born in Lima on June 8, 1928, Gutierrez completed his philosophy studies at the University of Louvain in Belgium and his theological studies in Lyon, France, and at Rome’s Pontifical Gregorian University before returning to Peru, where he taught at the Catholic university in Lima.

However, it was his pastoral work at a parish in Lima and as a theological consultant at the 1968 gathering of Latin American bishops in Medellín, Colombia — a regional meeting that aimed to adapt the conclusions of the Second Vatican Council to the Latin American context — that led to the development of his 1971 book, “A Theology of Liberation.”

While liberation theology’s call for a preferential option for the poor and freedom from unjust social structures resonated with many Catholics in Latin America, its politicization — particularly among those sympathetic with Marxist ideology — was at odds with the church, particularly during St. John Paul II’s pontificate.

At a meeting with Latin American bishops during his 1979 apostolic visit to Puebla, Mexico, the late pope, without explicitly mentioning liberation theology, warned of certain forms of humanism prevalent at the time entering the church, most notably, an “inexorable paradox of atheistic humanism” that gives “a strictly economic, biological or psychological view of man.”

“The Church has the right and the duty to proclaim the Truth about man that she received from her teacher, Jesus Christ,” he said. “God grant that no external compulsion may prevent her from doing so. God grant, above all, that she may not cease to do so through fear of doubt, through having let herself be contaminated by other forms of humanism, or through lack of confidence in her original message,” the pope said.

Müller told OSV News that liberation theology was not centered “in a political or sociological sense, but in a theological sense” in that “liberation comes (through) Jesus and goes in all dimensions.”

“And that liberty is the heart of freedom, it is the heart of our relation to God in the Holy Spirit, and this must also have consequences for our social life,” he said.

Gutiérrez’s teachings about a preferential option for the poor, the cardinal explained, were not so much about poverty in “a romantic sense” but rather in “the real sense that so many people in Latin America are living below the possibility of the dignity of human beings that don’t have (anything) to eat and to drink.”

“The consequence of the liberation in Jesus Christ must also be the experience of the dignity of human existence, of personal and social existence,” Müller said.

The former prefect for the Vatican’s doctrinal office told OSV News that Gutiérrez was more “concrete” in his thinking, often “going directly into the problems,” which is reflected in his development of liberation theology.

“The theology of liberation is first a judgment of the situation and then its evaluation in the light of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. And the third part is the praxis, the realization of these ideas in concrete life,” he said.

In the 1990s, the then-Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, led by the future Pope Benedict XVI, expressed concerns about some currents of liberation theology, which he said were politicized and relied on Marxist ideas and analyses. However, he also praised liberation theology’s zeal for social justice and the poor.

Pope Francis followed his predecessor’s line, disagreeing with the movement’s politicization while sympathizing with its concern for the poor.

Nevertheless, he also thanked Gutiérrez’s contributions to the Catholic Church in a 2018 message for his 90th birthday.

In his letter, the pope thanked the Dominican priest for his contributions “to the church and humanity through your theological service and your preferential love for the poor and discarded of society.”

“Thank you for your efforts and for your way of challenging everyone’s conscience so that no one remains indifferent to the tragedy of poverty and exclusion,” the pope wrote. “I encourage you to continue with your prayer and service to others, giving witness to the joy of the Gospel.”

Echoing those sentiments, Müller told OSV News that Gutiérrez’s theological work will leave a lasting contribution to the Catholic Church in seeing “signs and the peculiarities of the time” and to view them through “the light of the Gospel” that leads not only to change in pastoral practice but “to change society, the conditions of life and to make it better according to (everyone’s) dignity.”

“This, I think, will be his legacy,” Cardinal Müller said.

Gustavo Gutierrez was truly a great man. A friend, then a newly ordained priest from my part of the world, spent time in his diocese and everyone knew that the Rome of John Paul II was out to get him but they never did because Gustavo was too clever for them.

Also, I always thought that Müller used their friendship to gain a bit of respectability and street cred.

God rest him.